Reprising this from when I read E. G. West’s fascinating Education and the Industrial Revolution, which is a powerful argument for the conclusion that … well, let’s first look at some data.

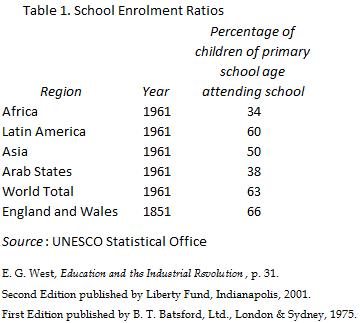

Here’s a table comparing school enrollments in various parts of the world with enrollments in England and Wales a century earlier.

The table shows that by 1851 the English and Welsh already had a higher percentage of children in primary school than the world total was over a century later. That’s an impressive accomplishment.

“What may be more remarkable to some,” West notes, “is that the British schooling was entirely voluntary and almost entirely fee-paying“[1, italics added]. That is, the British educated their children without compulsory attendance laws and almost without taxation.

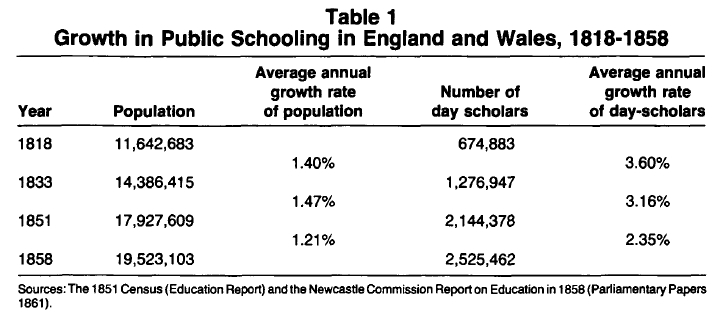

Another of West’s charts shows that — again without compulsion — the rate of increase in school attendance was about double the rate of population growth.[2]

Sources:

[1] E. G. West, Education and the Industrial Revolution, Second Edition, Liberty Fund, Indianapolis, 2001, pp. 31, 32. (First Edition published by B. T. Batsford, Ltd., London and Sydney, 1975.)

[2] Edwin West, “The Spread of Education Before Compulsion: Britain and America in the Nineteenth Century,” 1996.

Related: Stephen Hicks interviewed by Reliance College’s Marsha Enright on the essence of liberal education:

So, what’s your conclusion?

It’s an enthymeme, with that left as an exercise for the reader.

Ok. This particular reader thinks that the data presented “is a powerful argument for the conclusion” of nothing whatsoever.

If education can be accomplished that way, they why do we “need” compulsory public schools supported by mandatory taxation?

Bret, it seems clear to me that the issue Professor Hicks is focusing on is compulsion as the necessary means to the satisfactory education of our young.

Looking at early 19th century America Alexis De Tocqueville noted that virtually every American was reasonably well educated – and he was writing of a nation barely past infancy. Since then the state has taken on the role of being the primary educator of our young. The results have been abysmal.

Generations of children became guinea pigs in experiments that sought to socialize children at the expense of their cognitive development (John Dewey’s “progressive education”) – as if these were zero-sum to each other. On becoming adults, droves of them entered college and university poorly literate and often barely able to read.

Universal state funded and administered education means state funded ideas. And if, as above, an educational experiment fails, there is no competitive alternative or corrective.

A universally educated citizenry is a worthwhile goal but like every other good and service I think one best served by liberty.

Shit. Your answer is better than the whole post. Awesome.