Current infant mortality rates are about half of one percent, and it is awful for parents who lose a child. But in the 1700s, before the achievements of the Enlightenment were widespread, infant mortality rates were over 50%.

I came across this in Robert K. Massie’s Catherine the Great: Peter the Great (1682-1725) and his wife had twelve children — “six boys and six girls, only two of whom survived past age seven” (p. 29). Both survivors were girls, one of whom became the Empress Elizabeth.

Other prominent examples:

* The historian Edward Gibbon (1737–1794) was the only one of six sons to survive to adulthood.

* Wolfgang Mozart (1756–1791) had six siblings, and five of them died in infancy.

* The composer Franz Schubert (1797-1828) had thirteen brothers and sisters, and nine died in infancy.

The great reduction since then is thanks to modern medicine. Yet modern medicine depends on two things: lots of wealth and lots of free and vigorous scientific inquiry. Wealth in turns depends on economic freedom. Worth keeping in mind when evaluating those forces now at work to limit speech, control business, and de-legitimate science.

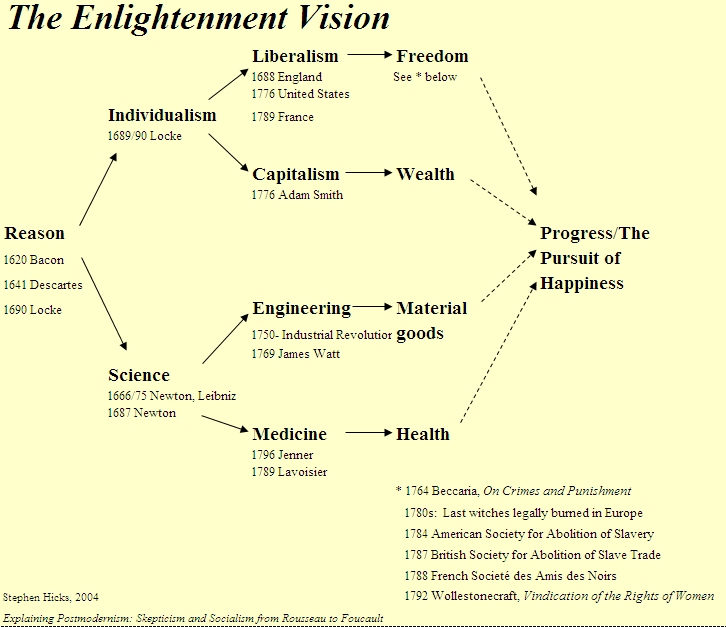

Related: Chapter 1 of Explaining Postmodernism: Postmodernism versus the Enlightenment.

Your “thanks to modern medicine” link doesn’t work. I’d be interested in seeing the source.

Standard historical analyses of the reduction of infant mortality attribute it to a variety of sources, including policies that involved extensive government intervention into the economy. A major factor was sanitation: filtration and chlorination of the water supply, the construction of sanitation systems, the development of statistics on birth and mortality rates, and public education of expectant mothers, all played an important role. All were provided by government.

It’s not clear how these things would have been provided by the private market ab initio (as opposed to being privatized after the fact), or whether there was (or is) any economic incentive for providing them on a private market on the same scale as government at all.

Beyond that, even the development of obstetrics and its application depended in large part on the subsidization of medicine to the poor, often at taxpayer (not merely charitable) expense. The scientific development of obstetrics per se is compatible with an improvement in mortality figures for the rich, leaving the poor exactly where they were for lack of access to obstetric services.

Here are some sources supporting the preceding, but the view itself is pretty standard:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30883959/

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.0800221105#:~:text=Early%20historical%20decreases%20in%20infant,use%20of%20antitoxins%20and%20vaccines.

As T.R. Reid notes in The Healing of America, there are no existing health care systems that combine positive clinical outcomes with a reimbursement system that imposes the full cost of care on individual patients. As a historical matter, either you have positive clinical outcomes with third party payment, or you have poor clinical outcomes. But third party payment is exactly what advocates of free market health care oppose, and precisely on the grounds that even if private health insurance is involved, third party payment reduces the individual’s responsibility for payment of total incurred charges.

If you want positive clinical outcomes, you need third party payment, but where you have third-party payment, whether private or governmental, you have a system of accounting controls imposed on health care providers. From a clinician’s perspective, there is little difference between a rule imposed by Aetna and one imposed by Medicare, or a denial issued by Cigna and one issued by Medicare. The rule demands compliance, and the denial denies payment.

https://www.amazon.com/Healing-America-Global-Better-Cheaper/dp/0143118218

It’s worth noting that while the US has a more capitalist health care system than any other First World country, it has the worst infant mortality of any comparable country, and ranks near the bottom of the OECD countries. These are the pre-pandemic 2019 figures:

https://www.americashealthrankings.org/learn/reports/2019-annual-report/international-comparison

The causal arrows in your diagrams omit almost all of the salient explanatory factors here.

While modern medicine is very expensive, and requires a lot of wealth, it’s worth noting that you can have a health care system like ours, sloshing in wealth, that produces very poor health care outcomes because the wealth is so poorly distributed across the system. It certainly is not true that the wealthier the system, the better the clinical outcomes, abstracting from all questions of allocation.

I was once somewhat sympathetic to libertarianism, but no longer am, and the defects of the libertarian-Objectivist view of health care is one of the main reasons. The tension between egoist ethics and capitalist politics is clearer in this case than any other: if health is in your self-interest, then a system that systematically fails to produce good health outcomes is not. But it simply is not true that the more capitalist the system, the better the health outcomes. So the tension remains unresolved.

I’ve read my share of books and articles on free market health care over the years, and have not found any of them (or any combination of them) convincing. If anyone reading this has a recommendation to make, I’ll take it under advisement, but appeal to infant mortality statistics is definitely not going to do it.

Your points here, Irfan, raise a set of topics that are additional and complementary to the points I make in the post. Yet you frame your discussion as contrary to my points. So in making your comments, (1) please don’t do that, and (2) please don’t assume what my views are on those additional/complementary topics, especially when (3) the assumptions you make there involve lumping me in with a large and diverse number of (unnamed) individuals.

(A more general point about your occasional appearances here at my site: I know you’re an intelligent guy, but you come across, metaphorically, as a shotgun with a hair-trigger just waiting for an excuse to blast away. So please slow down, ask a clarificatory question or two, and try to set a civil and perhaps even a benevolent context for further discussion.)

I won’t bother coming back. That’s not an honest response to what I wrote, and there are, I’ve learned, diminishing returns to engaging with a dishonest interlocutor. So keep playing whatever passive-aggressive games suit you, Stephen. I’m going to send this, click out of your website, and go wash my hands.

You’re still doing it, Irfan.