Excerpt from Mill Series Lecture, Lafayette College, 2018.

Questioner: [What is the difference between Jordan Peterson and you about the origins of the Enlightenment of the 1700s?]

Stephen Hicks: The big divide is between those who want to give equal credit to the Judeo-Christian tradition and to the Greco-Roman tradition. People who are more culturally conservative and politically conservative will say: Yes, we have the Greco-Roman tradition that’s absolutely important to us. It’s not accidental that Plato and Aristotle and Seneca and Cicero are cited and that all of our political architecture is Greco-Roman, and that we do our theater a certain way. And we all know what the Hippocratic Oath is. And we know who Euclid and Archimedes are. So yes, absolutely. But they will also say that equally important is the Judeo-Christian tradition, that there are strongly positive contributions that come out of the Judeo Christian tradition. And what makes modern Western civilization unique is that it is this hybrid of those two very deep traditions.

I don’t agree with that position. But I don’t think it’s a stupid position—it can be a sophisticated position with good arguments made for it.

The other position says that, yes, the Judeo-Christian tradition obviously has been important. The Greco-Roman tradition has been important. But if we’re trying to explain the positive achievements of the Enlightenment, the Greco-Roman tradition is more important. That’s the view that I take.

The kind of evidence that I cite here is that if you look at Europe, the Christians basically had Europe all to themselves for about 1,000 years [c. 300-1300 CE]. And what did they do with it? Well, they then say—this is an article I’m writing now—that you have to talk about Scholasticism, and the development of universities, and this and that other invention, and so on. I think all of that is true. But if you start putting dates to all of those things, that’s 1300s. That’s 1400s. And all of that is after the Greek and Roman texts are rediscovered and being reintroduced into Europe.

So what I think is that people who are strong fans of the Judeo-Christian tradition are making their peace with the modern world, but wanting to get some of the credit for it themselves.

My view is that it’s not to say that everything in Judaism and Christianity is wrong, but as a matter of historical development that they have been more of an obstacle than an assist in the development.

What had to happen was that a brilliant mind like Thomas Aquinas’s in the 1200s was exposed to the writings of Aristotle that had been recently rediscovered, and his teacher Albert, Albert the Great, and with his intellectual integrity and honesty saying: I think the Judeo-Christian tradition is absolutely right but I also am very impressed with the Greeks and Romans did and what this Aristotle guy has come up with, so let’s try for a synthesis. Aquinas is a unique individual who comes along.

But it’s also important to note that Aquinas was almost excommunicated for trying to do that synthesis. And it took a lot of student activism, for students who say: No! More Aristotle! More Aristotle in the curriculum!—imagine that—for the authorities to relent. And so the cat was out of the bag.

So I see the Judeo-Christians as fighting a rear-guard action, and then coming to accommodations with the increasing inroads of humanism, of the full-blown Renaissance, and so forth.

I do give the Reformation some credit, but I see it as unintended consequences. The early reformers, they hated Aristotle. You read what Martin Luther has to say about Aristotle—my goodness. Hate speech? Yeah, absolutely.

Luther had a very rich vocabulary, shall we say. And the same thing for Calvin, for Zwingli, all of the others. What they’re very much interested is going back to a purified, fundamentalist form of Christianity. From their perspective, now by the 1500s, the Church has sold out to Aristotelianism and become more worldly—and that’s a corruption of Christianity, so we have to get back to true Christianity.

But to their credit, what the Protestants did say is: We think the Catholic Church is corrupt in a theological way. The important thing is for each individual to have a direct relationship with God and not to have to go through this institution that says that God talks to the Pope who talks to the Cardinals, and so on, and/or is captured in Scripture. But Scripture is only available in Latin. And the vast majority of people can’t read their own language, let alone Latin. So the Protestants said that the important thing is for the individual to get a direct relationship with God, and the only way for an individual to do that is to know God’s word. And that means we need to start teaching people to read and to get the Bible translated into all of the vernacular languages.

Now, the Protestants’ purpose was not to cause the Enlightenment. But once you start teaching people to read and you start giving them books in their native language, then people start to read the Bible, and they start to try to interpret it for themselves. And you and I, in our Bible studies, have different interpretations. And so we started to have arguments about that. As a result I get better at argument, you get better at argument. And so we start to get more rational. And once people start to get rational and think that evidence and argumentation becomes important, that starts to fit into a certain kind of epistemology that’s developing in the early modern world. So the cat’s out of the bag, and the Protestants did, to some extent, let the cat out of the bag.

Now, fortunately, what we then have is the Protestants making that unintended contribution, the Catholics making their accommodations with Aristotelianism and, to this day, saying faith and reason are equally important—Revelation is important, but also Aristotle is very important. So both of them are indirectly contributing.

So I do think we can say positively, that the Judeo Christian tradition did add some things. But by a large margin, the most important traditions are coming from the Greeks and the Romans as they are reintroduced in Humanism and the Renaissance.

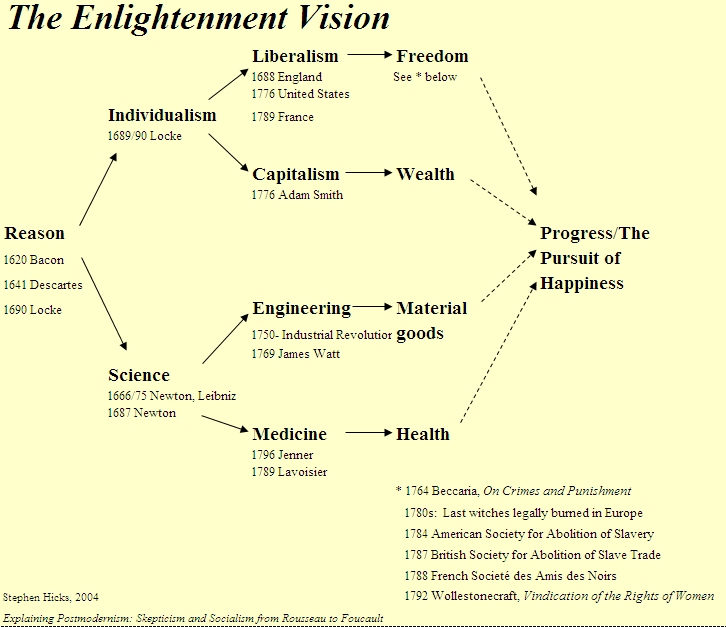

Questioner: One quick follow up. Jordan Peterson, and the author of the book Inventing the Individual (whose name I can’t remember) both argue, I think, that Christianity, and perhaps Judaism as well played an important role in spreading the idea that individuals are divine fragments, that they are made in the image of God, and that notions of the sanctity of the individual, which would lead to the political liberalism prong of your chart, and be attributed to Christianity.

Stephen Hicks: Very good. And again, I don’t think that is a stupid argument or a bad argument. That argument can be very well made. But I don’t find it very convincing. Because again, for 1,000 years, the “sanctity of the individual” rested very easily with serfdom, with slavery in many parts of Europe, with the second class status of women. And if you take seriously what it says in the Bible, I don’t know of anything in the Bible that says anything condemnatory of slavery at all. One mark of a commitment to the sanctity of individuality is repugnance against slavery and other forms of subordination.

The other thing I would say is, you can say “the importance of individuality,” but that has to be interpreted the way a strong Judeo-Christian person would interpret it. Namely, that what makes you importantly an individual is your soul. It is not your body, your body really is not that important, and the strong versions of Christianity that say what happens to your body doesn’t matter. And that means all kinds of subjugation can happen so as long as your soul is free.

But then, even if we are interested in the importance and the sanctity of the soul, that is complicit in the very long tradition of Christians—Jews are off the hook on this one, as far as I know—Christians being willing to torture people for extended periods in order to try to convert them.

And the argument is precisely the sanctity-of-the-individual-soul argument. If you really care about saving people’s souls, that it’s so important, what that means is that they have to get the right beliefs about Christianity. And so when people who have the wrong beliefs about Christianity are close to dying, if they die believing the wrong things, what’s going to happen is they are going to burn. So out of Christian love, therefore, you should torture their body and be willing to torture their body because that’s the only way, apparently, you can get them to listen. And maybe it’s not that successful, but you might get people’s attention enough and get a certain number of people on their deathbed under torture to convert, and therefore you have saved their souls.

So individual sanctity is an important principle, but the Christian record on it and how its interpreted, I think, is subject to lots of riders, both textual and historical. So I would de-emphasize that [in explaining the foundations of the Enlightenment].

Now, that’s not to say that the Greek and the Roman record is any better. I think there are some original additions that the Humanists came up with. Because as we know, the Greeks and Romans were fine with, the Greeks especially, a certain measure of slavery, second-class status of women. The Romans, I think, were a little bit better on both of those things. But the record is not perfect there. What you find is the germ of those ideas in the Greek and in the Roman tradition. And then what the achievement of many of the Renaissance thinkers, the Renaissance Humanists is to say: Wow, the Greeks and the Romans had these ideas and, not to discount the Judeo-Christian importance of the individual soul either, but they are taking that and elevating it into a much more universal principle.

And then we get to the Enlightenment, as late as the 1670s and 1680s. It’s really taking John Locke and others of that generation finally to write A Letter concerning Toleration and for the first political acts of toleration to be put in place. The Dutch more informally, had put toleration in place in the earlier part of the 1600s. Less on philosophical reasons, it strikes me in the Dutch case, it was more pragmatic: you’re just get sick of all the religious wars, and say “Okay, let’s stop all the fighting and get down to business,” and so forth. But that’s late 1600s. In Renaissance and Christian Europe.

Questioner: Just to follow up on Brandon’s question about the individual sanctity of the individual. The conversation that we were having was regarding my opinion on, on how the Greeks, for the first time in the history of humanity, represent in art the human being as beautiful. And in that specifically is the individual as a divine being, the concept of the best of the best, or what we might call God, or the logos, or which the Greeks mean. The Christians then pick up the concept of the logos that started with the Greeks: Is this infinitely complex wonder that we’re observing and is staring us in the face, that it could be represented in mankind in art. And it’s that when the Christians have the seat of power they have they destroy that. And it’s what’s picked up again in the Renaissance, when the Christians are actually losing power, that they use realism as a point of propaganda to try and …

Stephen Hicks: Sorry, who’s using realism as a point of propaganda?

Questioner: The Christian.

Stephen Hicks: The Church now? Excuse me, at what time are we now—Renaissance?

Questioner: Right. So that specifically is one of the elements that the Protestants turn away from in the north, and so then you have a difference in the northern Renaissance and the southern Renaissance. So this was our conversation about it.

Stephen Hicks: So we do the history of intellectual life through art history, which is a beautiful way to do it.

The first point, yes, is about the significance of Greek art and the statuary that has come down to us. And it is important that the portrayals of humans is humans as god-like, but also the portrayals of the gods as human-like. So you don’t have this radically Other conception [of the super-natural]. Nor the idea that humans should cower and fall to their knees and press their faces in to the dirt in the presence of something that is immeasurably greater than they. We humans can stand straight up. There’s a Jordan Peterson referencing, right? I guess I’ve got to have my shoulders back.

We can aspire to god-like status and the gods and goddesses are often portrayed as just superior human beings, more like—when I’m talking with my students about this—like the way when you’re a 13-year-old how you look up to your brother or your sister who’s 16 or 17. And they are Wow. And they are Power. But you also have a sense that you—with some effort and some growing—you could be there as well. And that is quite unique in art history. So, yes, that valorization and idealization of what is possible for human beings.

And it is striking that early Christianity, is—in the more radical sects, we have to be a little more nuanced here—are clearly reacting to that [Greek idealization], and in a negative fashion. Because their view is that the human being is, to use St. Paul’s words, sold into slavery to sin. We are worthless, smutty, grubby, we understand what’s good but we’re not willing to do so. And so your proper attitude should be one of self-loathing. And so any sort of Greek and Roman idealization is just going to be a slap in the face, and you’re going to want to destroy it. And so there was widespread destruction [of art].

Then, as you mentioned, that was picked up again, in the 1500s, when the Renaissance takeover because by then the Catholic Christians had made their compromises and were building beautiful cathedrals and decorations and paintings and so on. And one of the things that Protestants do is to go through and whitewash all of the frescoes and destroy a lot of the statuary in an effort to go back to pure Christianity.

There is, in addition to that Humanistic point, a kind of a metaphysical theological point that should also be emphasized if we’re going to talk about art. That is a point about graven images. It is a Commandment that thou shalt not make graven images. On the basis of that, whole fields of art then become metaphysically suspect. The argument then is, if you are trying to take something that is ineffable, spiritual, supernatural and capture it in physicalistic form—well, that’s a sacrilege, that’s a blasphemy, because you can’t take something that is so wonderful and special and defile it by representing it in in physical form, and it certainly wouldn’t be a human form.

So I think that’s, in part why there are not graphic traditions or sculptural traditions and painting traditions in some of the major Western religions. Judaism has a strong literary tradition, but not much of a painterly or sculptural tradition, because they take that Commandment seriously. The Christians took it seriously for 1,000 years. It was a huge debate in the 1100s about whether, when we’re building these great new Gothic cathedrals, we should allow these emerging artists inspired by the Greeks and Romans to start putting Bible stories on the walls. Because they are saints, they are demigods, so whatever status the various Christian heroes have, but again we have this “Shalt not make graven images” and that makes it seem a little bit sacrilegious.

But the argument that prevailed, from my reading of the history, is to say: Well, we do have all of these, to put it bluntly, illiterate people who are getting bored after the third hour of the priest’s droning on in Latin and they’re looking around, we might as well make good use of that time. So maybe we can compromise and have some illustrations of Bible stories give them something uplifting to look at while they’re in church. Then they can absorb some of the messages. But that was seen as a compromise on the theological point. And it’s precisely that compromise on that theological point that the Protestants are going to react against and reject a few years later in trying to get back to the purified form.

* * *

Related:

Jordan Peterson interviews of Stephen Hicks: Postmodernism: History and Diagnosis (August 2017) and Postmodernism: Reprise (May 2019).

St. Augustine on benevolent torture.

The full Stephen Hicks Mill Series lecture at Lafayette College, Pennsylvania (October 2018).

PDF version of above transcription.