What does God think of human reason? In my courses, I like to emphasize that early in modernity the old and the new were in stark contrast.

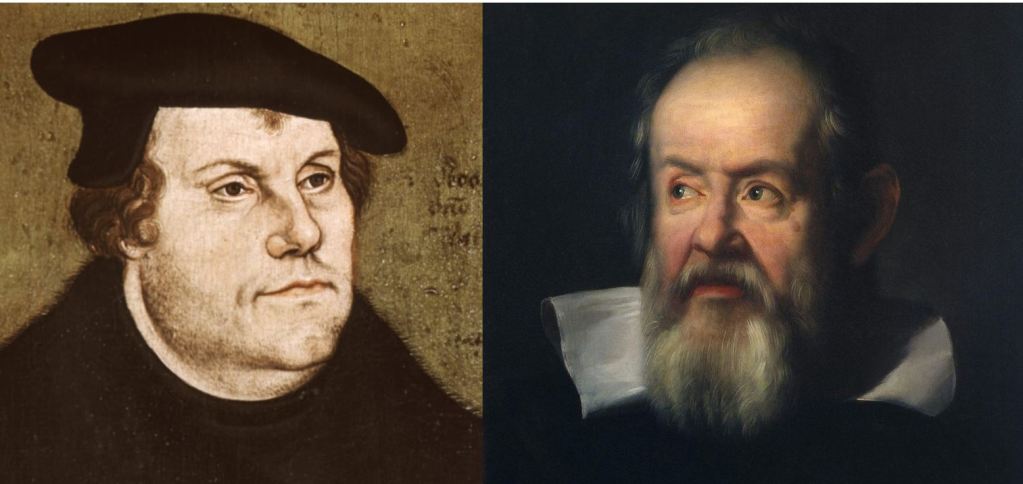

Here is Martin Luther, reacting against Renaissance Humanism and the more worldly Aristotelian direction of Christianity in the late Middle Ages:

“In this whole matter the first and most important thing is that we take earnest heed not to enter on it trusting in great might or in human reason, even though all power in the world were ours; for God cannot and will not suffer a good work to be begun with trust in our own power or reason.”

And here in contrast is Galileo Galileo, representing the new scientific spirit:

“But I do not feel obliged to believe that that same God who has endowed us with senses, reason, and intellect has intended to forgo their use and by some other means to give us knowledge which we can attain by them. He would not require us to deny sense and reason in physical matters which are set before our eyes and minds by direct experience or necessary demonstrations.”

Sources:

Open Letter to the Christian Nobility of the German Later, concerning the Reform of the Christian Estate (1520).

Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina (1615), https://www.stephenhicks.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Galileo-Letter-to-Christina-text-1615.pdf.

Imagine thinking a Protestant reformer as symbolizing the “old”.

🙄

I have a suggestion:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/0674987136/ref=cm_sw_r_cp_apa_i_7RyoFbW84RDCG

Returning to the “old” and original religion was exactly the reformers urged, as opposed to the “new” compromises and worldliness they saw as corrupting it.

2/3 rds of the founding members of the Royal Society were clearly in the Puritan camp – which was a heterodoxy of Calvinism. They adopted the idea of Atomism of Democritus and Lucretius – which stood in direct contrast to the Aristotelian physics and metaphysics of the Roman Catholic (and to a large degree, the Anglican) Church. Galileo got in trouble with the Church by claiming that there were mountains on the moon – meaning, that the heavily bodies were not perfect spheres of pure ether, as had been claimed by Aristotle (and the Church). The parable about Newton and the Apple is that Newton realized that heavenly bodies followed the same physics as terrestrial bodies, i.e. they are made of the same stuff. And early experiments by the Royal Society members rejected the Roman Catholic – and Aristotelian – belief that there were only 4 terrestrial elements (earth, water, air and fire) and that they were infinitely divisible.

In the 17th Century, philosophy, science and religion were inseparable. And you couldn’t really choose bits of pieces from the Roman Catholic (Aristotelian) ideas and the newly introduced ideas of Atomism. Newton, Locke Galileo, etc. were clearly and openly non-Aristotelian.

Jacob Bronoswski’s book book, “The Western Intellectual Tradition, from Leonardo to Hegel” and Richard Westfall’s “Science and Religion in 17th Century England” are two wonderful books about the establishment of modern science and the conflicts with the commonly held views of the Roman and Anglican Churches.