[Grégoire Canlorbe is a French intellectual entrepreneur. He currently resides in Paris. He interviewed me for The Foundation for Economic Education. Excerpt below:]

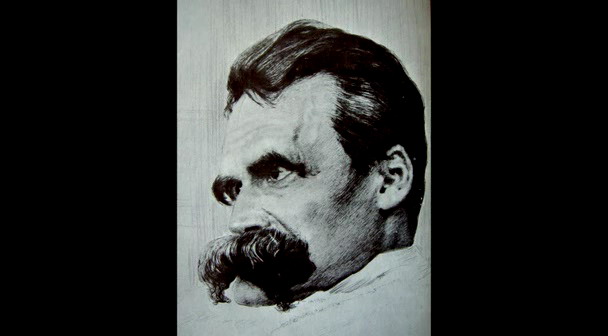

Grégoire Canlorbe: Both Rand and Nietzsche vehemently despise the ancestral notion of “Common Good”, dating back at least to Aristotle. Nietzsche eloquently and provocatively sums up his grievances against it in paragraph 43 of Beyond Good and Evil.

“One must renounce the bad taste of wishing to agree with many people. ‘Good’ is no longer good when one’s neighbor takes it into his mouth. And how could there be a ‘common good’! The expression contradicts itself; that which can be common is always of small value. In the end things must be as they are and have always been — the great things remain for the great, the abysses for the profound, the delicacies and thrills for the refined, and, to sum up shortly, everything rare for the rare.” Beyond Good and Evil, chapter II, paragraph 43.

Nietzsche and Rand are generally thought to be similar and treated on an equal footing by academics. Would you say that their respective criticisms of the notion of “Common Good” are indeed convergent or, on the contrary, divergent?

Stephen Hicks: I once counted the similarities and differences between Nietzsche and Rand on 96 major philosophical issues — metaphysical, epistemological, ethical, and political. They agree on 19 of those issues but they disagree on 70 of them (and on seven issues it’s arguable one way or the other).

So it is a shallowness when academics who should have done their homework generally lump them together.

But Nietzsche and Rand do share some important similarities, and one of those is negative — their loathing of collectivism and altruism, precisely defined.

“The common good” is one of those ambiguous phrases that give people trouble. Does it mean (a) one common goal that everyone is supposed to be working towards — e.g., everyone should be doing his part to build the pharaoh’s pyramid? Does it mean (b) a resource that everyone uses as a commons — e.g., the air in the Earth’s atmosphere that each person draws upon individually? Or does it mean (c) a general category of values that are in fact unique and particularized — e.g., every mother’s love for her own child is special and distinct but we can put their experiences into a common category?

The brilliant quotation you cite from BGE is a clear statement of Nietzsche’s elitist anti-common-good position. It does nicely capture that many great things are difficult and so only a few in any population will strive for them and achieve them. For Nietzsche this is not a journalistic but a philosophical truth about people: the large majority of people are by nature incapable striving for—much less achieving—anything great. For Rand it is a philosophical truth that anyone born with normal capacities can strive and achieve greatness—and a journalistic truth that many people betray their own potentials.

The difference then is that the Nietzschean may feel an aesthetic disgust for the vulgar and the common, but the logic of that position is that no moral condemnation can be made: The sheep, the slaves, and the ressentiment types can’t help being what they are. But for Rand, the choices that individuals make are more significant to who they become and what they value, and so her evaluations can be both aesthetically and morally charged.

One also suspects that for the Nietzschean any great value that comes to be appreciated by many people would for that reason alone cease to be greatly valued. For example, only a few genuinely appreciate the greatness of Rembrandt’s portraits and Rachmaninoff’s concertos. But suppose that with effective cultural education Rembrandt and Rachmaninoff became generally and genuinely admired and appreciated. For the Nietzschean, hoi polloi’s enjoyment would undermine his enjoyment — it’s no longer exclusive, so he can’t define himself in contrast to them any longer.

For Rand, by contrast, it would be a great achievement if we could get everyone to appreciate Rembrandt and Rachmaninoff. If they really are great, then one’s experience of their greatness can and should be independent of others’ evaluations.

In that respect, Nietzsche is much less individualistic than he is often made out to be.

Here is a PDF of the full interview.