Here’s a conversation I’ve had many times over the years with colleagues in business ethics and related fields. I’m at, say, a conference and someone will profess disgust at something a large corporation has done:

Colleague: Look at this bad thing that Microsoft/ Walmart/Facebook/Amazon did. Corporations have way too much power in this country.

Me: What do you mean by “too much power” here?

Colleague: It’s practically a monopoly. It really should be broken up.

Me: What do you think, then, about the US Postal Service? Should it be broken up?

Colleague: What? Why?

Me: Well, it’s an actual monopoly, lots of customer complaints, loses tons of money …

Colleague: Well, no, that’s different.

Me: Really? Why?

Colleague: … [after a pause, usually something about needed public services, benign monopolies, or tradition].

The USPS is my go-to example about monopolies — but none of these conversations has ever, to my knowledge, led to a colleague’s thinking seriously that the USPS should be broken up, privatized, or let go out of business.

Setting aside the USPS’s coercive power to put competitors out of business, setting aside its many privileges (e.g., being tax-exempt), and focusing only on the financials, see page 2 of this 2018 report from the Department of the Treasury:

“The USPS is forecast to lose tens of billions of dollars over the next decade. Further, as of the end of FY 2018, the USPS balance sheet reflects $89 billion in liabilities against $27 billion in assets – a net deficiency of $62 billion.”

(I’m reminded of the huge scandal when Enron went bankrupt to the tune of some amount over $60 billion.)

So what explains the mindset: X is bad/scandalous/horrible if done by a private business — but if X is done by a government body … shrug/not-a-big-deal. Why the asymmetry?

Related:

“Who Is Really Serious About Monopolies?” Also in Portuguese translation.

Let’s propose a few answers

1. “Disparate impact”.

When a private business makes profit (especially “excess profit”) that goes to the owners, not the community.

When a private business goes bankrupt, the owners are last in line, behind creditors and employees – ie. the community.

When a state run business makes “excess profit” that goes to the community.

When a state run business goes bankrupt (or is subsidised), the community are on the hook but they stand behind employees.

There’s an expression popular amongst pundits in the UK – privatise the profits and socialise the losses which summarises the position.

This is a moral argument

2. “It will reduce the cost of the product/service”

In my mind this is so incorrect as to be barely worth offering but it is a widely held belief, so it must be given consideration.

In practice this supposition is not borne out. Much of industry was nationalised in the post war UK, including railways, utilities, motor industry, steel making, coal mining, telecoms, health service. Some was already loss making like the railways but much of the rest became loss making over a period of years. When the bulk of it of was privatised in the 1980s much returned to profitability (particularly telecoms, & utilities) but much remained loss making. I’ll pick out two factors that contributed but there are many others: (1) much of the estate needed modernisation after the war and there was no money to do that – ie railways continued to use steam for two decades (2) the original objective was subverted for other political ends: eg. Steel Plants were built in places of high unemployment rather than in the logical places near to raw material or other facilities. Or rationalisation did not occur when appropriate because of political considerations – eg. no one was going to close a plant causing job losses or risk closing loss making rail lines when was a marginal constituency.

3. Fundamentally though, I think there’s a deeply ingrained sense of profit being a dirty word. It’s not regarded quite “wicked” as usury but it’s close. This is in psychology territory. It’s odd that people expect interest from savings in the bank but manage to divorce this from their personal dislike of businesses making a profit. There’s something related: I notice that businesses go though a lifecycle. When a startup, perhaps small, there is a sense of “yes they deserve the rewards”. So Amazon, Google or to pick a non tech – Body Shop (UK) started life as “cool” but later on their lost that and started to be regarded as a bit dodgy. Amazon and Google are past that and are now in the positively “wicked” stage.

>The USPS is my go-to example about monopolies

See also:

– American Medical Association (which artificially caps the number of resident MDs to push up wages and was described by Milton Friedman as the most pernicious cartel in America)

– Social Security (which is compulsory and has a negative rate of return for an increasing number of Americans)

>Why the asymmetry?

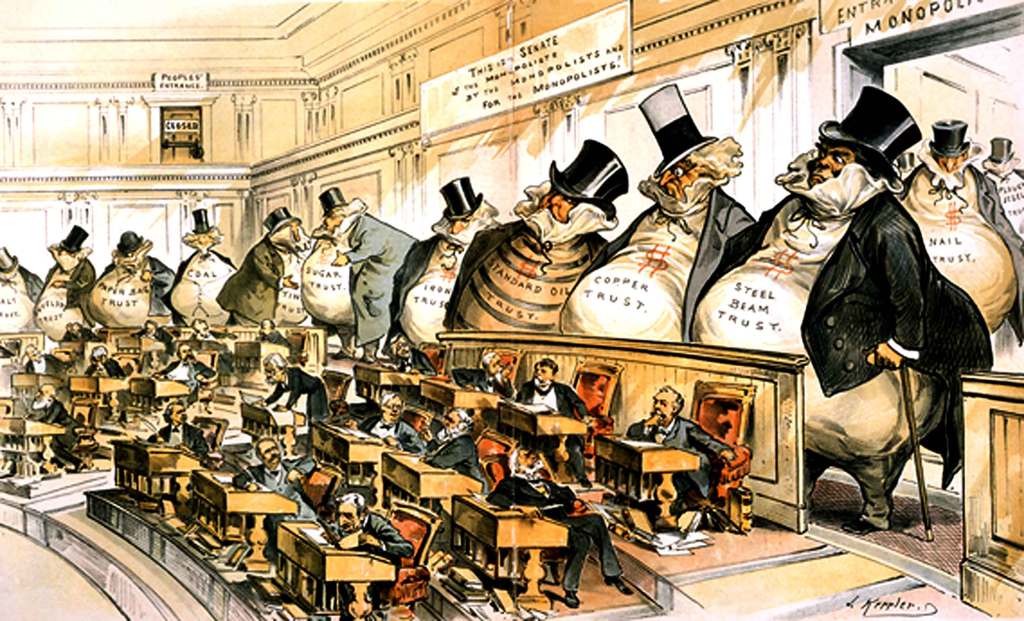

Because anti-monopolists are generally anti-capitalists. The USPS examples shows they’re typically not proposed to monopolies per se, rather opposed to privately-owned profit-making monopolies.

The USPS while being a monopoly, has little opportunity to become institutionally corrupted from a board room level due to its leadership turnover and governmental oversight and public reporting accountability. A whole scale private corporate monopoly is quite a different beast and when family owned, can possibly become a monarchy of corruption through generations. The Post Office doesn’t bear this option of generational corruption.

The usps is owned by, highly regulated by the federal government. If we regulate all monopolies like the post office, by choosing who runs it, fire ceos we don’t like, where they can open stores, dictate how much profit they can make, and put all profits back into the fed coffers, then sure please, for the love of God regulate monopolies!