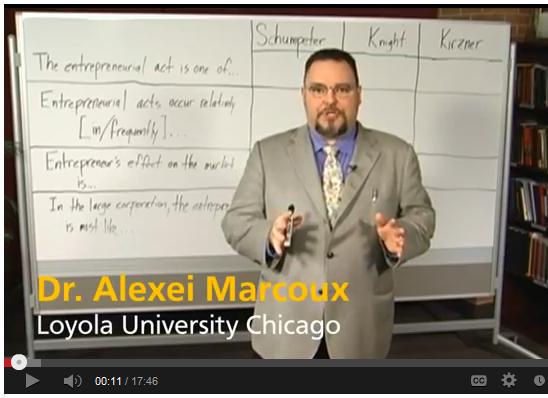

[This lecture is Part 1 of the Entrepreneurship and Values series and was recorded at Rockford University and sponsored by the Center for Ethics and Entrepreneurship.]

Dr. Alexei Marcoux on Defining Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship as an Essentially Contested Concept”

I want to talk today about entrepreneurship and, in particular, its status as an essentially contested concept. By an essentially contested concept, what I mean is that most people, if not all people, believe that entrepreneurship is very important, even as they disagree about what entrepreneurship is. I want to illustrate the disagreement about what entrepreneurship is by considering three seminal thinkers about entrepreneurship: Joseph Schumpeter, Frank Knight and Israel Kirzner. By looking at the way each characterizes entrepreneurship, we will see that even as they tend to agree about who, among people in the world, are entrepreneurs, they disagree significantly about what it is that those people are doing that is an entrepreneurial act. Let’s start with Schumpeter.

For Joseph Schumpeter, the entrepreneurial act is essentially a creative act. It is from Schumpeter, it is from Schumpeter that we get the phrase ‘creative destruction’ to refer to entrepreneurship. You know, if you’ve never thought about entrepreneurship before, chances are that most of your thoughts about entrepreneurship come from Joseph Schumpeter. That’s because, for Schumpeter, the entrepreneurial act is essentially innovative. In today’s economy, we tend not to be able to talk about entrepreneurship without talking about innovation. This is a Schumpeterian inheritance. For Schumpeter, the entrepreneur is somebody who brings a new product, process or way of doing business to the market. The entrepreneurs essential contribution then is a novel contribution. The entrepreneur emerges as a disruptor of what is going on before. If you think about entrepreneurship in the context of the neoclassical ideal of the perfectly competitive market, the entrepreneur comes in to an equilibrium situation in which commodity products are being bought and sold and upsets the harmony or the equilibrium of market by bringing a new product or process or business model to that market. So, for Schumpeter, it is the creative, the innovative act that it is the entrepreneurial one.

For Joseph Schumpeter, the entrepreneurial act is essentially a creative act. It is from Schumpeter, it is from Schumpeter that we get the phrase ‘creative destruction’ to refer to entrepreneurship. You know, if you’ve never thought about entrepreneurship before, chances are that most of your thoughts about entrepreneurship come from Joseph Schumpeter. That’s because, for Schumpeter, the entrepreneurial act is essentially innovative. In today’s economy, we tend not to be able to talk about entrepreneurship without talking about innovation. This is a Schumpeterian inheritance. For Schumpeter, the entrepreneur is somebody who brings a new product, process or way of doing business to the market. The entrepreneurs essential contribution then is a novel contribution. The entrepreneur emerges as a disruptor of what is going on before. If you think about entrepreneurship in the context of the neoclassical ideal of the perfectly competitive market, the entrepreneur comes in to an equilibrium situation in which commodity products are being bought and sold and upsets the harmony or the equilibrium of market by bringing a new product or process or business model to that market. So, for Schumpeter, it is the creative, the innovative act that it is the entrepreneurial one.

Compare Frank Knight. From Frank Knight, we get the fundamental distinction between risk, on the one hand, and uncertainty on the other. Although in ordinary discussion today, we tend to treat risk and uncertainty interchangeably, in fact, we use the word risk to refer to both. Knight, in his 1921 book, Risk, Uncertainty and Profit, argues that risk and uncertainty are as different as night and day. To be in a risk situation is to know the full range of outcomes that can occur as well as to be able to put reasonable probabilities to them. To be in an uncertainty situation, by contrast, is to find oneself in a situation where either one does not know the full range of outcomes that can occur or, alternatively, one cannot put reasonable probabilities to those outcomes. For Knight, the entrepreneur is not so much a person who brings novel things to market as in the case of Schumpeter. For Knight, instead, the entrepreneur is someone who bares the uncertainties of the enterprise. Now, what does it mean to bear the uncertainties of the enterprise. Well, that’s something we are going to get to in a moment by way of considering who, in modern, large corporation, is or is most likely the entrepreneur. Something we will get to in a moment.

Compare Frank Knight. From Frank Knight, we get the fundamental distinction between risk, on the one hand, and uncertainty on the other. Although in ordinary discussion today, we tend to treat risk and uncertainty interchangeably, in fact, we use the word risk to refer to both. Knight, in his 1921 book, Risk, Uncertainty and Profit, argues that risk and uncertainty are as different as night and day. To be in a risk situation is to know the full range of outcomes that can occur as well as to be able to put reasonable probabilities to them. To be in an uncertainty situation, by contrast, is to find oneself in a situation where either one does not know the full range of outcomes that can occur or, alternatively, one cannot put reasonable probabilities to those outcomes. For Knight, the entrepreneur is not so much a person who brings novel things to market as in the case of Schumpeter. For Knight, instead, the entrepreneur is someone who bares the uncertainties of the enterprise. Now, what does it mean to bear the uncertainties of the enterprise. Well, that’s something we are going to get to in a moment by way of considering who, in modern, large corporation, is or is most likely the entrepreneur. Something we will get to in a moment.

Israel Kirzner has a different view of what it is to be an entrepreneur. For Kirzner, the entrepreneurial act is not so much an act of creation as it is an act of discovery. An entrepreneur is someone who perceives an opportunity and then, having perceived the opportunity, acts on it. This falls out of Mises’s idea that all human action begins out of what Mises calls ‘felt uneasy’. An entrepreneur, in Kirzner’s understanding, is somebody who perceives the difference between what is what could be. And by virtue of having perceived that difference, undertakes to act to pursue what could be as opposed to what is.

Israel Kirzner has a different view of what it is to be an entrepreneur. For Kirzner, the entrepreneurial act is not so much an act of creation as it is an act of discovery. An entrepreneur is someone who perceives an opportunity and then, having perceived the opportunity, acts on it. This falls out of Mises’s idea that all human action begins out of what Mises calls ‘felt uneasy’. An entrepreneur, in Kirzner’s understanding, is somebody who perceives the difference between what is what could be. And by virtue of having perceived that difference, undertakes to act to pursue what could be as opposed to what is.

So, for Knight, the entrepreneurial act is one of bearing uncertainty. For Kirzner, the entrepreneurial act is one of perceiving opportunity. We can see the significance of the difference in each thinker’s account of what entrepreneurship is by considering how each thinker would complete the sentences that are started on the left side of the board here. We said earlier the entrepreneurial act is for Schumpeter, the action is creation; for Knight, one of bearing uncertainty; for Kirzner, one of perceiving opportunity.

The next sentence we might try to finish is Entrepreneurial acts occur relatively … and the answer or the completion of that can be either frequently or infrequently. Because Schumpeter focuses upon novelty and the novelty of the creative act, the creative act that undoes the existing equilibrium and creates a new norm in the economic order, Schumpeter tends to hold that the entrepreneurial act occurs in infrequently. Many people bring things to market, but only some of the things brought to market tend to undo the existing order.

Think, for example, of the way VHS technology in the 1980s undid BETAMAX, although many people believed that BETAMAX was a superior technology, VHS was good enough and it was also cheaper. As a result, it displaced BETAMAX in the market. It didn’t destroy BETAMAX; BETAMAX became a niche product that was used in professional video production for a number of years. So, when Schumpeter talks about creative destruction, that destruction can either be a case of putting a business firm out of business, or, more likely, taking once mainstream product or technology and turning into a marginal one. So, for Schumpeter, entrepreneurial acts occur relatively infrequently.

Now, to complete the statement for Knight, to complete the statement for Knight, we have to consider what does it mean to bear the uncertainties of the enterprise? I think to understand Knight you have to think back to an important figure, not a particular figure, but an important ideal character in American History. This is the person, usually a man, for the time Knight is talking. This is a person who works a job, saves up money until this person can finally quit the job and then start his or her own business. In an earlier era in American history, we talked about wanting to start a business to that I can ‘be my own boss’. This is what it is to bear the uncertainties of an enterprise, because, what it is to be your own boss is to give up the security of a paycheck in order to eat what you kill, right, that’s what Knight is talking about. And, in a very dynamic, market-oriented, entrepreneurial economy, this sort of activity — starting a business — so that you can be your ‘own boss’ and eat what you kill, is something that occurs relatively frequently.

Now, for Kirzner, the entrepreneurial act is not found so much in the pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunity as it is in the perception of entrepreneurial opportunity. So, an entrepreneur is someone who perceives a difference between what is and what could be in the world and then goes on to pursue it. As a result, because Kirzner understands all human action to have an entrepreneurial element, Kirzner believes that entrepreneurial activity occurs frequently.

Now, what is the effect of the entrepreneur upon the market? We’ve already talked about Schumpeter idea that the entrepreneur is a disruptive force. Schumpeter has in mind the idea that a market is commoditized and so you have many buyers and many sellers, selling what is fundamentally the same product until along comes an entrepreneur with an innovative product that upsets that equilibrium and displaces what was there before. For Schumpeter, the entrepreneur is like the stone thrown into a plastic pool, where once the pool is still and flat, when the stone is thrown into it, it creates ripples in the water. What happens is the entrepreneur thereby sets a new standard and just as the pool of water eventually recomposes itself into flatness and stillness, the once innovative product becomes the new commodity. So the entrepreneur, at least when engaging in the entrepreneurial act is this disruptive or disequilibrating force.

I want to skip over to Kirzner for this, because I think his answer is more clear than Knight’s is. For Kirzner, by contrast, the entrepreneur’s effect upon the market is very different. That’s because Kirzner, as Austrian economist, understands disequilibrium to be the natural state of the economy. In disequilibrium, there is a gap between supply and demand; there is a gap between what is being supplied in the market and what it is that people want. And the entrepreneur is someone who perceives that gap. As a result of perceiving that gap, the entrepreneur then takes action which, if successful, tends to bring what is supplied in the market and what is demanded in the market into greater equilibrium. So, as a result, Kirzner sees the entrepreneur’s effect on the market as harmonizing or equilibrating, that is, there are entrepreneurial opportunities. There are entrepreneurial opportunities in the market precisely because it is indeed disequilibrium. If the market were in equilibrium, there will be no opportunities for the entrepreneur to perceive.

So, the question is: how does Knight answer this question? Does he understand the entrepreneur to be an equilibrating force or a disaquilibrating force? For Frank Knight, the fundamental entrepreneurial role is that of bearing the uncertainties of the enterprise, so, the uncertainties of the enterprise, of course, things like will the firm be profitable or will it not? The entrepreneur is the one who eats what he kills rather than taking home a stable paycheck? When viewed through that lens, I think it’s clear that for Knight the entrepreneur effect on the market is equilibrating.

Think of it this way: when a firm is being created, we need somebody to be the residual risk-bearer in the firm, to either collect the profits or suffer the losses. That role going unfilled is evidence that there is disequilibrium in the marketplace. So, Kirzner, Knight, Schumpeter and complete the statement “The entrepreneur’s effect on the market is …” differently. Probably, the best way to illustrate the difference between Schumpeter, Knight and Kirzner on entrepreneurship is to consider the large publicly traded corporation. In the large publicly traded corporation, the entrepreneurial role is sliced and diced through the process of the division of labor, that is, what is once embodied in a single entrepreneur becomes farmed out to different functionaries within the corporation. And so, an interesting question to ask is: for Schumpeter, for Knight and for Kirzner, who is or is most like the entrepreneur in the large, publicly-traded corporation?

Now, for Schumpeter, the answer, the short answer is: It could be anybody. It could by anybody because there are several places in the enterprise that innovation, that novelty, can occur. It may be an engineer; it may be an engineer who creates a new product. It may be somebody in production who creates a new process for making an existing product that makes it more profitable. It may be someone in marketing, who identifies a new way to market an old product or thinks of a new product that can now can be marketed to an existing sector of the market. So, for Schumpeter, it can be anyone who innovates and there are several places, of course, within the large publicly-traded corporation where innovation can occur and so, as a result, any of those people could, if they are engaged in innovative activity, that brings a new product or process to market. That person is engaged in entrepreneurship and is or is as close as one can be to be an entrepreneur in the large publicly-traded corporation.

For Knight, the answer is remarkably straightforward, because, in the division of labor that is the large publicly-traded corporation, the residual risks of the enterprise are a portion to the shareholders. It is the shareholders in the large public-traded corporation that either collect its profits, whether through dividends or through an increase in the stock price, motivated by an increase in retained earnings, or who suffer its losses. Losses that are manifest through a decrease in the stock price or in the ultimate case the collapse of the enterprise, in which case the shareholders get nothing out of it. The shareholders are the one who more than anybody else, within the large publicly-traded corporation, are bearing the uncertainties of the enterprise and so they are or the closest to being the entrepreneurs within the large publicly-traded corporations.

Now, for Kirzner, the entrepreneur is somebody who perceives an opportunity and so the answer for Kirzner is a little bit like the answer for Schumpeter, except by virtue of the fact that we are talking not about the innovation, but instead, the perception of an opportunity to profit, right. For Kirzner, it would be more likely somebody who is engaged in marketing or sales or something like that. An engineer would not be somebody who would be perceiving opportunities so much as they would be engaged in innovation. So, whereas an engineer might be a likely case of an entrepreneur for Schumpeter, it wouldn’t be so much for Kirzner.

And so, I think we can see that even these three thinkers would probably find a lot of agreement in pointing out people in the world who are entrepreneurs. There are very different things about the entrepreneurial activity that each is pointing to say what entrepreneurship ultimately is.

[The video of this lecture by Dr. Alexei Marcoux follows.]