In the following two passages, with a nod to Tocqueville, Mill makes two strong claims.

First he praises American culture: “Almost all travellers are struck by the fact that every American is in some sense both a patriot, and a person of cultivated intelligence. … No such wide diffusion of the ideas, tastes, and sentiments of educated minds, has ever been seen elsewhere.” (Thanks for the pat on the back, J.S.!)

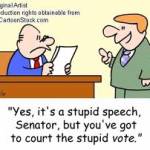

But he follows with this about American politicians: “political life is indeed in America a most valuable school, but it is a school from which the ablest teachers are excluded;  the first minds in the country being as effectuallly shut out from the national representation, and from public functions generally, as if they were under a formal disqualification.”

the first minds in the country being as effectuallly shut out from the national representation, and from public functions generally, as if they were under a formal disqualification.”

Mill published that 1.5 centuries ago, but comparisons to the present are apt. He is talking about democratic-republican politics, which he thinks is better in most respects than the alternatives. But it has its own weaknesses, one being the types of people it attracts and repels from political life. So some follow up questions, if this really is a systematic problem in our politics.

First: Are politicians really less able than the first-rate people in other walks of life — scientists, physicians, business executives, artists? How would we determine this?

Second: If so, what is it that makes politics less attractive to the most able and more attractive to the moderately able?

Is it that smart and able people better see the compromises involved and the damage to their integrity? Or the scrutiny of their personal lives? Or they are interested less in wielding power over others than they are in positive values such as seeking scientific truth or building a great business or creating artistic significance?

And by contrast, are the moderately-able are more willing to be compromisers? They are less able to be first rate scientists, artists, or business professionals, so they are more likely to seek significance through power over others?

Or is it that in our political system, elections are decided by marginal or moderate voters, and that fact in some way creates a lowest-common-denominator dynamic?

Other factors? (Please avoid ad hominem and other cheap shots abut particular politicians. Mill is pointing us to a systematic problem, not the foibles of particular individuals, parties, or generations.)

Source: John Stuart Mill, “Of the Extension of the Suffrage,” Chapter VIII of Considerations on Representative Government (Easton Press, 1995; originally published 1861), p. 157. Also available online here.

Source: John Stuart Mill, “Of the Extension of the Suffrage,” Chapter VIII of Considerations on Representative Government (Easton Press, 1995; originally published 1861), p. 157. Also available online here.

I think that Ayn Rand captured the issue, as one of second-handedness and selflessness versus independence and rational selfishness.

Business is all about wealth creation and trade, not about collective dependence, but individual independence; not about self-sacrifice, but about rational self-interest; not about charity, but about profit. In business, in a free market, one is good due to one’s rational, intellectual independence and productive ability. In politics, one is good due to one’s ability to voice and act upon the dominate moral view(s), to give “the people” what they truly and predominantly want, to lead them where they most want to go.

Depending on one’s moral views, business is either profoundly good or perhaps a tolerated, necessary evil requiring eternal vigilance and governmental control. Likewise, depending upon one’s moral views, collectivism, in various forms, is either profoundly good or profoundly evil, or individualism is profoundly good or profoundly evil.

Politics is all about morality. Politics rests on morality, and it is the culturally dominant moral views that inform and guide politics. The only way to argue what ought to be legally or politically is by reference to some code of morality. It doesn’t work the other way round.

Altruism is the culturally dominate ethics or morality of America and the world. Bill Gates was a good businessman prior to becoming a philanthropist, but was he held to be an exemplar of morality, or did he only start to become morally admired once he decided to take on the role of philanthropist?

The “public good” is not questioned, but held to be the fundamental guide for political policy. “Public good” trumps individual rights, which is but another way of saying that individual rights are not the fundamental issue of a proper government, of politics, of law. When push comes to shove, that which is held as primary trumps anything else.

So we get politicians who are first-rate in the area of politics guided by altruism, and the “best” rise to the top promising their focus on and concern for the “public good.”

A politician is “good” if he appeals to the “public good,” to altruism, to self-sacrifice. They are selfless leaders for a culture that fundamentally or dominantly values self-sacrifice for the “public good,” for the good of society. They are “good” because most or a great number of people tell them that they are good.

“Isn’t that the root of every despicable action? Not selfishness, but precisely the absence of a self. Look at them. The man who cheats and lies, but preserves a respectable front. He knows himself to be dishonest, but others think he’s honest and he derives his self-respect from that, second-hand. The man who takes credit for an achievement which is not his own. He knows himself to be mediocre, but he’s great in the eyes of others. The frustrated wretch who professes love for the inferior and clings to those less endowed, in order to establish his own superiority by comparison.” – Ayn Rand, “The Nature of the Second-Hander”

Of relevance, here’s an 8 minute, 2010 interview of Thomas Bowden, from the Ayn Rand Institute, by Brad Davis on the subject of Hugo Chavez’s socialism and the morality that supports him:

http://arc-tv.com/hugo-chavez/

Dr. Hicks, here’s an article by Dr. Andrew Bernstein, which I’ve only just read, that gets to the heart of the matter:

“Objectivism vs. Kantianism in The Fountainhead” (The Objective Standard):

http://www.theobjectivestandard.com/issues/2012-spring/objectivism-kantianism.asp

Thanks very much, John. I will check it out.