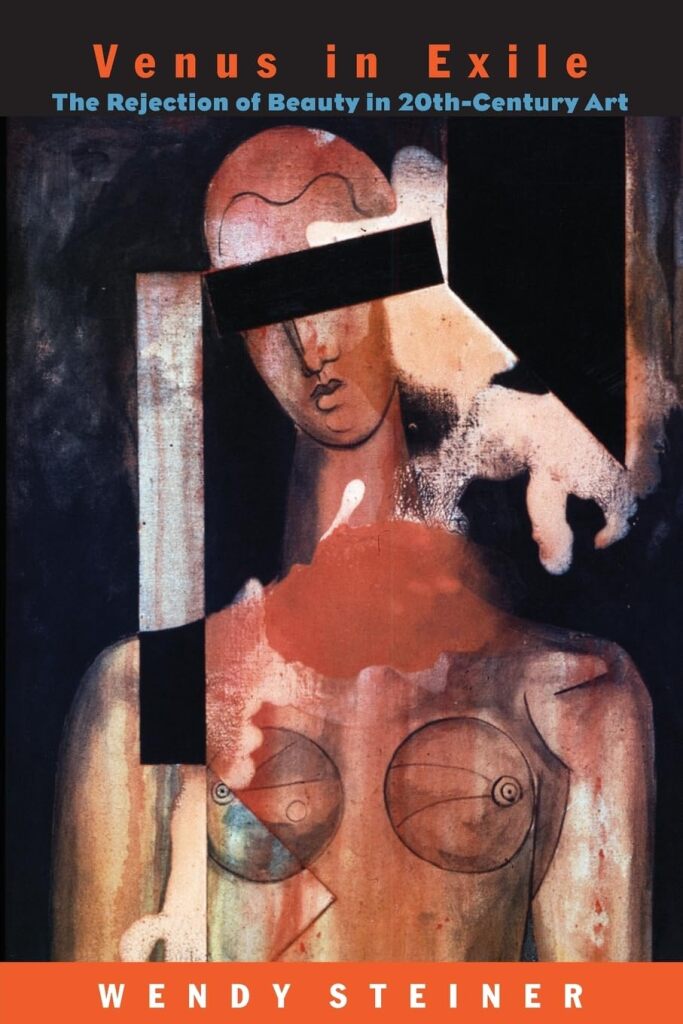

In her Venus in Exile: The Rejection of Beauty in 20th-Century Art, Wendy Steiner, a professor of literature at Penn, argues that “In modernism, the perennial rewards of aesthetic experience — pleasure, insight, empathy — were largely withheld, and its generous aim, beauty, was abandoned” (p. xv).

Steiner notes that “the main symbol of such beauty, the female subject,” especially was abandoned in the twentieth century. “The avant-garde were utterly hostile toward the ‘feminine aesthetics’ of charm, sentiment, and melodramatic excess, which they associated with female and bourgeois philistinism” (pp. xxiv-xxv). (See also: Were the Modernist painters misogynist?)

All of which raises the question: Why? Steiner’s first statement of her thesis is that the experience of beauty is a profoundly relational experience. In philosopher-talk, it is neither purely an intrinsic feature of the object nor a purely subjective state. We are moved by the object, and “in our gratitude toward what moves us so, we attribute to it the property of beauty, but what we are actually experiencing is a special relation between it and ourselves” (p. xxiii).

Beauty is a connection between the self and the Other, but it also generates an elevating action component: “finding something or someone beautiful entails becoming worthy of it — in effect, becoming beautiful, too — and recognizing oneself as such” (xxiii). One is thus energized and challenged by the beautiful Other and “rises to recognize oneself in it” (p. xxiv).

Steiner’s account seems to imply that the full experience of beauty requires that one be a certain kind of person — capable of being so moved, of thinking oneself worthy and beautiful, of being energized to elevating challenges. That in turn seems to imply a profoundly different aesthetic for a profoundly different kind of person. What if, for example, one’s deepest sense of being is of estrangement, self-doubt, of an unbridgeable gulf between oneself and others, of alienation from reality?

The previous paragraph is my interpolation, but I was struck by the next step Steiner’s analysis, introducing “the Kantian sublime, which was the aesthetic model for high modernism” (xxiv).

In the Kantian sublime, Steiner points out, there is a supreme disconnect between the self and the Other. It is “specifically the non-recognition of the self in the Other, for the Other is inhuman, chaotic, annihilating.” The self realizes “the immensity of this gap” and is left “unfastened, unconnected to the object of its awe” (p. xxiv). There is no mutuality and no connection possible, so no action is worthwhile. One can only persist in the more sublime-relevant emotions of fear or awe or passive submissiveness. The Kantian sublime is an aesthetic of profound alienation.

And thus some groundwork is laid for Modernism’s “violent break” from the rest of art history.

Sources: Steiner, Wendy. 2001. Beauty in Exile, The Rejection of Beauty in 20th-Century Art. The Free Press. More quotations from various scholars connecting the Kantian sublime and modernism in art: Kant and Modern Art and More on Kant and Modern Art.

Related: In Norway, discussion of Kantian philosophy and artistic modernism, with Jan-Ove Tuv:

Also related: My “Why Art became Ugly” and lecture in Buenos Aires, Argentina at ESEADE University.