Interview conducted at Rockford University by Stephen Hicks and sponsored by the Center for Ethics and Entrepreneurship.

Hicks: Our guest today is Professor Nicholas Capaldi, who is the Legendre-Soulé Professor of Business Ethics at Loyola University in New Orleans.

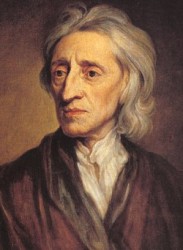

Professor Capaldi was here lecturing on business ethics. You framed your discussion on business ethics in terms of two broad narratives that have dominated the modern political thought and modern cultural thought: the Lockean and the Rousseauian. So, let me first ask you to summarize the main ingredients, so to speak, of the Lockean narrative. How does that go?

Capaldi: I call it, technically-speaking, the Lockean liberty narrative, and then I would flash that out in comparison to the Rousseauian equality narrative because I think the meaning they give to those terms tells you a lot about where they going. I would make a couple of very broad historical claims, namely, that there has been this ongoing debate or discussion between Lockeans and Rousseauians over a long period of time. And I will even strengthen the historical claim by saying that all the major spokespersons in public policy debates, etc., at one point or another, are defending or attacking either the Lockean or the Rousseauian point of view. To piggyback here on a Keynes remark, just as politicians are invoking some dead economist through a philosopher they haven’t read, I would say that a lot of contemporary theorists are repeating, in contemporary rhetoric, arguments that have been around since Locke first expressed his view and was critiqued by Rousseau.

Hicks: Is it fair then to say, in a historical context, as feudalism was declining, being overthrown, then the question in the modern world is: What are we going to replace it with? And we have two answers, a more Lockean answer and a more Rousseauian answer? Fair enough?

Capaldi: Sure. Locke is looking at this, even philosophically, from a very different point of view. He is thinking of wealth in a post-feudal world as something that is not finite, but can grow.

Hicks: Okay.

Capaldi: And it grows through labor and what we’ve come to call technological projects. So, industry, technology, etc. He is in a universe, in his mind, which is capable of potentially infinite growth. He thinks that this growth would be enhanced through a market economy. And in those places where Locke discusses market issues, he clearly comes out in favor of a market being as free as possible. He is certainly very famous for arguing in favor of limited government, and he thinks government should be limited in the interest of freeing the market economy. When he discusses legal matters he is a proponent of what has subsequently been called the rule of law, which, put in simple terms, means you put as many limitations as possible on government discretion so that it doesn’t overstep its bounds and interfere with the market. And finally, in many ways the most important point he makes is that none of these institutions can be understood nor can they work unless you have a certain kind of person, a person we’ve come subsequently to call the autonomous individual, and this is very important to Locke. Now, Locke’s assumption is that society is started on a contract. He means this in a metaphorical sense, but he understands a contract to mean the following: that all negotiation in the contract begins from the status quo. That you can’t have any negotiation unless you begin from status quo. That certainly privileges some people over other people.

Hicks: In the initial position…

Capaldi: In initial position. Now, Locke is not worried about that because he thinks that the emphasis should be on growth. And as long as the economy is growing, the question is not what we start out with but what can we make with what we start out with. And so, theoretically…

Hicks: With open-ended potential?

Capaldi: Yes, open-ended potential. So that’s why in a sense, Locke never worries about equality of outcome. He’s focused on equality of opportunity, and then he would think that people who have less than others do not, on that basis alone, feel that something is wrong. What they are focused on is their opportunity to grow within that.

Hicks: So in the Lockean framework, then, we’ve got five ingredients: the first one is what you call the technological project. The technical project is the idea that resources can be acted upon to increase the net stock.

Capaldi: Right.

Hicks: The second one is the free market economy, limited government, rule of law, and then this individual responsibly. A strong notion of self-responsibility, self-empowerment, right, and so forth.

Capaldi: Right, one of the reasons I use the culture of personal autonomy is that Michael Oakeshott wrote this wonderful article in which he says all modern moral philosophy begins with the focus on the individual and therefore raises problems about how the individual is going to be related to the group. And then he ticks off all the people that we take seriously in ethics that at some point focused on what it means to be a responsible individual. There is, historically speaking, a reaction to Locke well known in the writings of Rousseau which specifically rejects Locke’s notion of the original contract and argues that it’s unfair precisely because we are starting out from the status quo. There’s unequal bargaining power, the strong have somehow imposed upon the weak, and in Rousseau’s framework that delegitimizes all subsequent activity.

But even before that, Rousseau became famous in his first set of writings by attacking the whole notion of a growth economy. He doesn’t like technology, he doesn’t like science, he thinks that it leads inevitably to social stratification, and he would argue, as Marx would emphasize later, every social problem we have can be traced back to the fact that we got away from small agrarian republics. We should never have left that. Where people are relatively equal, nobody has much more than anybody has. So he was originally against the technological project, and the radical environmentalists with us today still pretty much argue the same position. Subsequent defenders of Rousseau modified that. So, for example, when you get to Marx, he is very much in favor of the technological project, but he goes along with Rousseau’s argument that the free market economy is exploitative and gives all the advantages to the people who had more in the original bargaining position. And Marx would also agree with all the other points that Rousseau makes.

Rousseau was not in favor of limited government. His most important political ideal is the notion of the general will. So Rousseau is trying to resurrect in the modern context, the classical notion of an enterprise society. That is, a society that has a communal goal, where individuals in fact do not stand out as we’re accustomed to thinking. He thinks that as long as the collective goals are kept in mind, and as long people work toward the common goal, then his system will work. And he would argue that the dysfunction that we see in the world today is the result of people following the Lockean model of thinking of themselves first and not worrying about the common good.

Hicks: Side question — this distinction between the enterprise associations and civil associations, from whom do we get that terminology?

Capaldi: All right, I borrowed that language from Michael Oakeshott because that’s where I first came across it, but you’ll find this kind of distinction being made all over the place. By Hayek, for example, when he talks about the different kinds of societies. And Tom Sowell has a book called The Two Visions where he talked about this division.

Hicks: Class divisions?

Capaldi: Right, exactly. And, interestingly, these are people are coming to the same conclusion from somewhat different perspectives. But Oakeshott’s notion is that a civil association, which he identifies with the anglo-American world, exists for the benefit of its members. It has no purpose other than to serve its members. An enterprise association does have a collective goal, and within an enterprise association, individuals have to subordinate their personal aims to what they are identifying as a greater good.

Oakeshott is not opposed to enterprise associations. He thinks that these are very important, but he also believes that the question is whether your overall society should be an enterprise association. So, for example, in the US, we have lots of enterprise associations, families, athletic teams, the military, belonging to a religious order, etc., but the overall structure is going to exist as a civil association, meaning it doesn’t have a goal of its own. So, looking at it from the government’s point of view, the function of the government is to do as much as possible to stay out of the way and to make it as much as it’s possible for individuals and smaller groups to do what they want to do.

So an example of a good law, to jump to Hayek, would be traffic laws. Everybody has to drive on the same side. It doesn’t matter whether it’s left or right as long as we all do it. But the traffic regulations don’t tell you where to drive, they don’t tell you should drive, etc. They simply facilitate the driving of the individuals. And that would be an example of what Hayek and Oakeshott would say the rule of law should ideally be.

Hicks: So, they are enabling and not directing. Now, you are describing a Lockean narrative. You said that, in your judgment, the most important element was the fifth element: the individual autonomy, self-responsibility, self-empowerment and so forth.

Capaldi: Right.

Hicks: Do you think it’s correspondingly true on the Rousseauian side, that the most important element is the sense of communal belonging, or collective responsibility?

Capaldi: Yes. You see this all the time when, for example, people will identify with a particular group. Or in public discourse when someone says, “It takes a village to raise a child,” to quote a recent Secretary of State. That sort of comment that we are all one big family is in the news today. As a metaphor it can be harmless, but I think in the minds of a lot of people what it is really saying is that we have to think of ourselves in terms of the community to which we belong. Now, the people who emphasize personal autonomy are not opposed to communal activity. It’s just that they think it should reflect the voluntary decisions of individuals, and, therefore, it would be a very different sense of community. If I can give what was a prejudicial example, marriages traditionally were understood in communal terms. You had a certain role that you had to play. Men were supposed to do this, and women were supposed to do that. Marriages were arranged. The community had to be there to sanction it because what you did was relevant to the community. I would say, nowadays, we emphasize that people should be autonomous individuals and not simply thought of in terms of their roles. I would argue that it makes it harder to be married today than it was in the traditional sense, but I also think that such marriages are, when they work, far more stable. People don’t feel trapped, and in those marriages people more likely to feel liberated than were in a traditional marriage. So, it’s not a question of whether people are going to engage in a joint action. It is the attitude that they bring toward the joint action.

Hicks: Would another way to put it fairly be to say that, for the Lockeans, the social organizations are a means to the ends of the individuals involved, but for the Rousseauians, the individuals are the means to the communal ends?

Capaldi: Absolutely. And in authoritarian societies, that has been the model going as far back as we have recorded this. And it’s only in the Western world and the post-renaissance period that we begin to see the alternative model. So, in a strange sort of way, maybe in an ironic sort of way, Rousseau is trying to preserve a classical or medieval conception of communal membership in the modern world. Let me use another analogy, and I don’t think I am stretching the point here. Before we talked about the five elements, the technological project, the market economy, etc. One of the problems we meet with the globalization is everybody pretty much wants all of the products of the technological project. What they don’t understand is that they’re going to have to change the way their economies are organized, the way their governments are organized, the way their legal systems are organized, and the toughest nut of all to crack, they’re going to have to change their cultures. And a lot of the problems you see in the world today are a result of this.

Hicks: So, without that cultural, legal, political infrastructure you’re not going to get the goods, so to speak.

Capaldi: Right. And so, for example, several of the problems one sees in Africa are a result of people who maintain a notion of tribal membership which actually inhibits them thinking even in terms of what would be mean to be an autonomous nation. To say nothing of that is what it would mean to be an autonomous person.

Hicks: Return to contemporary business ethics, where you do a significant amount of your work. You’re taking these two broad theoretical models that have long historical antagonism and debates and then applying it to debates within the business ethics profession right now. So let me talk you through some of the specific issues there. The subtitle of your talk was “How the Narratives Explain Everything” which is a good marketing point, but there might be truth to it so let’s see how far we can go. So corporations, for example, are perhaps the most dominant form of business organization in the modern world. How does the Lockean versus Rousseauian narrative explain how we think about corporations?

Capaldi: Okay. I would think that Ronald Coase’s comments on this reflect the Lockean point of view when he says that firms, and in this case corporations, are a nexus of contracts. So, you understand a corporation in terms of myriad number of overlapping contracts between and among different interest groups, all the way from suppliers in one end to employees at the other end. And management, for example, is a sort of clearing house for all of these contractual relationships.

Hicks: So, the bottom-up individuals?

Capaldi: Yes, and the emphasis is that you can’t attribute to the corporation a notion of an identity independent of the all the contracting parties that are involved in it. And, in a sense, the corporations have a life only as long as all of those contracting parties can agree to pull together, even though they have different aims of their own. If, on the other hand, you take a Rousseuain point of view, you are going to think of a corporation as a collective, as something that has been empowered by government and that somehow corporations themselves should serve some larger, social purpose. Now Locke would say that corporations serve a social purpose, they create wealth, they create products, services, and jobs, they pay taxes to local communities, etc. But, for Rousseauians, that’s not sufficient. They want corporations who actually get involved in solving or addressing a whole host of social problems. From a Lockean point of view, you don’t deny the existence of these problems. What you would say is that those problems are best solved by charities, by philanthropies, etc. Those charities and philanthropies are set up when individuals who themselves have been particularly successful in the business world decide to donate their money in order for that money to be used for a useful purpose. In a sense you might come to think of philanthropy as another form of enterprise, rather than the companies doing it directly. But if you are Rousseauian, you are very much against the notion that it should be left to the choice of individuals. Rather, the government should somehow be managing this by extracting rents from corporations, and corporations should be more focused on solving social problems.

If I can give a prejudicial example, let’s say that I was running a pharmaceutical company, and we were trying to come up with a cure for cancer. So, I would look to hire people, let’s say, and chemists on the basis of whether not these chemists showed promise in their individual work and their creativity to create some kind of scientific breakthrough. A Rousseauian might say it’s important that the chemists reflect the diversity of the society we live in order to serve as an inspiration to younger people to think that they too…

Hicks: So, they’re are getting into affirmative action kind of debate, yes?

Capaldi: Exactly, and the Lockean would say, no, that’s not what a pharmaceutical company should be doing. So, that’s the kind of debate that you would get about the purpose of a corporation.

Hicks: So, we have a terminological issue. In the course of your lecture you mentioned Ralph Nader in passing, and I am reminded at this point of the debate he had with Robert Hessen, an economic historian, over the nature of corporations. And one side, the Hessen side, was arguing that we should think of corporations as voluntary networks of individuals, what he called the contractual model. So, the individuals make the corporation, and the role of the government is just to respect the right of the people to form that sort of association. And the Nader position was more of a concession theory of the corporation that, in some sense, the government allows corporations to come into existence as long as the corporation is going to serve a government-approved purpose. Is that a fair description?

Capaldi: I think that’s a very good description of the distinction, and in a funny sort of way Nader is actually closer to the truth historically because, originally, corporations were founded as grants from kings, etc. But that has not been the case since the 1850s. In fact, since the 1850s, corporations obviously have become a special kind of economic vehicle that are capable of doing things on economies of scale that smaller enterprises were not capable of doing. Limited liability is absolutely crucial here, because it encourages people to take risks that they would not otherwise take. Also, while we are talking about the importance of competition, it is worth pointing out that one of the objections that has been raised to the recent Dodd-Frank legislation is that, in the past, different states in the United States would grant corporations. So I, for example, have a corporation that has its CEO from Louisiana, and perhaps the most important state in all of this is Delaware. So, the different states can compete with each other and have different rules and regulations. What is increasingly happening as a result of the financial crisis is that the federal government is more and more centralizing the rules, so we will lack the competition in the marketplace for corporations that used to exist if this current trend continues.

So it always gets back to two questions here: which is the more effective way of achieving your goal, through some kind of centralization or through some kind of competition? But behind that lies another dispute: what is the point, or what is it that you are trying to achieve? If you a Lockean, what you are trying to achieve is to increase the amount of opportunities as much as possible. And this will be beneficial to everybody. If you are Rousseauian, you are more focused on making sure that there is not a great disparity between the people at the top and the people at the bottom. So, while Rousseauians sometimes talk as if their intention is to make things more efficient, and there are people all for that argument, there are other Rousseauians, and these are becoming more and more prominent today, who are willing to give up efficiency in order to achieve greater equality of outcomes. So, that’s their focus, not creating more opportunities for everybody.

Hicks: We’re seeing it as a trade-off between efficiency and various other structural values?

Capaldi: That would be another way of putting it.

Hicks: So, corporations come into existence and have a certain status. If we go inside the corporation we have managers, and typically there is division of responsibilities between investors and professional managers who are brought in. Part of your model is to explain how managers should think of their function inside the corporation. So, what’s the difference there?

Capaldi: So, actually, I want to have a more radical model which I think does capture what Locke is about. There are people who have what is called the stakeholder model, where everybody in the universe who is somehow affected by the corporation should have a say in what the corporation does. Then, there are those who think that, no, the corporation is owned by the stockholders, and these are the people who are the most important.

Hicks: So we have the stockholder versus stakeholder debate?

Capaldi: Right, but I think there is a third factor here which is often overlooked. And that is, I would argue for what’s called the managerial model of corporations. I think the corporations exist to carry out the designs that the managers have in mind and that the stockholders are simply people investing in this because they like the idea and they expect some kind of return.

Hicks: Well, the division of labor, then, is the managers are providing the vision and the stockholders are providing the funds?

Capaldi: Definitely. They are providing the capital. They are creditors, but they are not any more special in this sense than any other creditor, say, banks or bondholders, etc. And keep in mind that the rules for this are not democratic, which is presumably the way Rousseauians would want to structure it. The number of votes even that stockholders get is based on the number of shares that they own. There is also non-voting stock in addition to voting stock. But I think that that conflict is still missing the point, is not understanding why a corporation is out there. Because the corporation is out there to create a profitable product or service, and the people who have the vision to do that are the ones who are running the corporation. The rest of us are contributing capital in order to make that happen. We have the expectation of a return, and also we hope that the products they create are things that we would want to buy as consumers. So, I think the emphasis should really be not on who the vested interest groups are, but whether you see the corporation as a dynamic entity, designed to create wealth, or whether you see the corporation in Rousseauian terms as more focused on the distribution of what the corporation produces rather than on the creation of what the corporation does.

Hicks: All right, that goes back to the first point about the technological project model. The Lockean emphasis is on taking resources and what we can do with them, and Rousseauians are more focused on distribution of preexisting resources.

Capaldi: Right. To put this in historical context, both proponents have ways in which they respond to the other side. Obviously, the Rousseauians would characterize Lockeans as people who are more focused on defending the status quo, giving rewards to the privileged. In a way, the anti-Wall Street movement protesters are reflecting a kind of Rousseauian perspective. And the Lockeans would argue in turn that the emphasis of the Rousseauians is misplaced. The purpose of this is to maximize opportunities for as many people as possible to do what they can with it. People do not resent having less than others. What they want is an equal shot at being able to succeed.

Hicks: Not having a sense that the rules are rigged against them.

Capaldi: Exactly. No force, no fraud, etc. You know, if you look at the technological project that makes sense. You can’t look at this the way people did in the Middle Ages, where the only major resource was real estate and the people who had the real estate held on to it pretty much forever.

Hicks: And it was a zero-sum game?

Capaldi: It was a zero-sum game. You know, people think of the business world as a monopoly game where the only way you can win is if everybody else loses. But the Lockeans don’t see the business world from that point of view. It’s not a two-dimensional board and a zero-sum game. It grows in every direction, and my growth is not at the expense of your growth. But, in fact, every time you grow, that creates opportunities for me to do things that would not otherwise be there for me to do. It’s a totally different view of the universe.

Hicks: Fair enough. One more question, stepping outside of what you talked about in your lecture, but you did mention the Occupy Wall Street movement. It makes me wonder if there is in contemporary business culture, particularly since it’s so politicized right now, a third type that is neither Lockean nor Rousseauian, the so-called crony businessmen. So, clearly, the Lockeans will be outraged at the cronies who are able to use politics to their own business advantage, and Rousseauians are also outraged. But they are outraged for different reasons. They diagnose the problem differently, and the ultimate solution is going to be different, but that type of crony business professional and the politicians that enable them, where do they come from if they don’t come out of the Lockean model or the Rousseauian model?

Capaldi: That’s a really good but complicated question. First of all, let me say that I think you are absolutely correct to point that crony capitalism is, in fact, what we have in the world today. And despite the differences you may see in the political parties, too often the leadership in both parties is just another form of crony capitalism in the sense that they have different capitalists who are their cronies.

Hicks: Of course, no matter the parties involved.

Capaldi: Right. One answer to give to that is that there are people who do not really see the big picture, and one thing you can say about it is that some crony capitalists really still see the world in zero-sum terms and are trying to grab up as much as they can. So, if we’re not going to identify people as just being evil — I am willing to do that, but it wouldn’t be helpful here — but evil aside, there are people who just don’t get what the long term value is to everybody, including themselves. After all, the members of the families of crony capitalists get sick too, and I wonder how they would feel about the fact that the pharmaceutical industry is not as effective as it should be. So, again, it is a very short term view. And the other thing is, in the kind of business climate we’ve had in this country since certainly the 1930s, there is so much government regulation that I can imagine someone saying, “I don’t like it. I don’t like crony capitalism, but in order for me to function, I have to spend so much of my resources combating the government and dealing with it that I may as well start to control the government in order to advance my interests.” So I would say, at the very least, it’s a combination of two things: Shortsighted people just don’t get it. There is no reason to think that because people are in business they really do understand how markets work.

Hicks: The moral hazard.

Capaldi: The moral hazard and then, of course, the misadventures of the government actually giving companies an incentive to do that. In fact, I would say a large part of the totally inexcusable behavior we saw in the financial world and the crisis of 2007/2008 was simply, “If the government is going to decide the things are too big to fail, I don’t have to worry about the irrationality of these government policies. I am simply going to take advantage of it to the extent that I can.” So, to give a rough analogy, if there is a bank down the block from where I work and every Thursday afternoon they throw 100 dollar bills out on the street, I would think that it was very irresponsible of them as a bank, but I know every Thursday afternoon I would be there trying to scoop up as many as I could. So, this is an insane system, but if that’s the way it works then the incentive is really encouraging me to be somewhat irresponsible. And I would also point out that there are some members of the business world who are extremely sophisticated, who really do get it and are really trying to work hard to adhere to the Lockean model. And usually what happens to those business leaders is that there are various entities in government who go out of their way to focus their persecution on business leaders who are not willing to play the crony capitalism game. That’s the story that has not been told as much it should be told.

Hicks: To try not to end on a negative note, we have a semi-functional or dysfunctional cronyist system dominant right now, and neither the Lockeans nor the Rousseauians are happy with it. You are more of a Lockean guy?

Capaldi: Yes, to be fair, yes.

Hicks: But we have this longstanding debate. What do you, as an academic, think is the most important intellectual step that needs to be taken to try to reform the system?

Capaldi: The thing that must be done is to educate the public about how economies work and what the limitations are.

Hicks: So, economic education?

Capaldi: Yes, economic education. Even if the majority of economists in the academic world today, and I think this is true, are Keynesians and are very heavy on the regulation side, I think that if the public knew more about economics, the level of economic discussion would go way up and politicians could then not escape having to give some sort of rationale for why they are advocating what they do. Just to take one example, President Obama recently talked about the changes that have to be made in Obamacare. He used the analogy of a recall in the automobile industry. Automobiles have to recalled on occasion. Now, if I take him literally on that, I would have to say that he is using a mechanical model of an economy. But economies are not mechanical systems and work in an entirely different way. If you have the wrong model, you are inevitably going to make mistakes in public policy. I would like to see the public say, “you know, maybe we have to be careful about our metaphors,” because a metaphor is maybe giving away intellectual positions that are very suspect. So, I think a lot more has to be done, but simply raising the level of discussion helps. I find that most academics don’t understand economics and that this is rarely discussed in the media unless you are devotee of Kudlow or something like that, you will not see these questions raised. But they would be raised if the public were more aware of what’s going on.

Hicks: All right, thank you very much for being with us today. Great material.

Capaldi: Thank you.