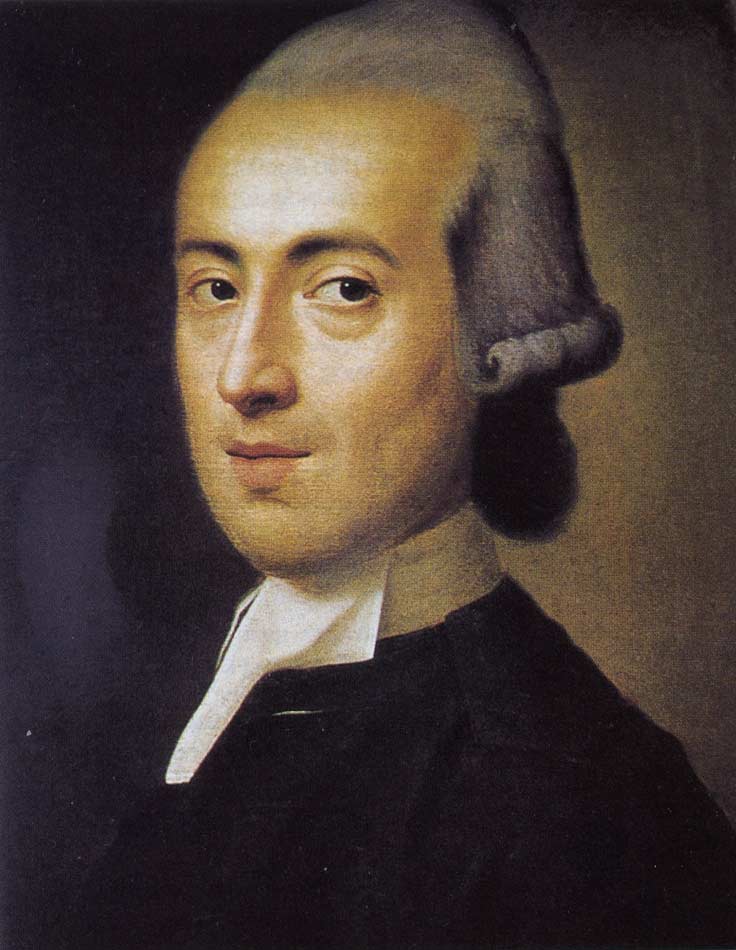

[Herder (1744-1802) was an early Counter-Enlightenment voice calling for group identity politics and value relativism, along with a rejection of cultural appropriation and an embrace of zero-sum cultural conflict. The following is excerpted from Explaining Postmodernism.]

Herder on multicultural relativism

Sometimes called the “German Rousseau,”[1] Johann Herder had studied philosophy and theology at Königsberg University. Kant was his professor of philosophy; and while at Königsberg Herder also became a disciple of Johann Hamann.

and while at Königsberg Herder also became a disciple of Johann Hamann.

Herder is Kantian in his disdain for the intellect, though unlike the static and rigid Kant he adds a Hamannian activist and emotionalist component—“I am not here to think,” Herder wrote, “but to be, feel, live!”[2]

Herder’s distinctiveness lies not in his epistemology but in his analysis of history and the destiny of humankind. What meaning, he asks, can we discern in history? Is there a plan or is it merely a random happening of chance events?

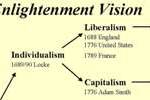

There is a plan.[3] History, Herder argues, is moved by a necessary dynamic development that pushes man progressively toward victory over nature. This necessary development culminates in the achievements of science, arts, and freedom. So far Herder is not original. Christianity held that God’s plan for the world gives a necessary dynamic to the development of history, that history is going somewhere. And the Enlightenment thinkers projected the victory of civilization over the brutish forces of nature.

But the Enlightenment thinkers had posited a universal human nature, and they had held that human reason could develop equally in all cultures. From this they inferred that all cultures eventually could achieve the same degree of progress, and that when that happened humans would eliminate all of the irrational superstitions and prejudices that had driven them apart, and that mankind would then achieve a cosmopolitan and peaceful liberal social order.[4]

But the Enlightenment thinkers had posited a universal human nature, and they had held that human reason could develop equally in all cultures. From this they inferred that all cultures eventually could achieve the same degree of progress, and that when that happened humans would eliminate all of the irrational superstitions and prejudices that had driven them apart, and that mankind would then achieve a cosmopolitan and peaceful liberal social order.[4]

Not so, says Herder. Instead, each Volk is a unique “family writ large.”[5] Each possesses a distinctive culture and is itself an organic community stretching backward and forward in time. Each has its own genius, its own special traits. And, necessarily, these cultures are opposed to each other. As each fulfills its own destiny, its unique developmental path will conflict with other cultures’ developmental paths.

Is this conflict wrong or bad? No. According to Herder, one cannot make such judgments. Judgments of good and bad are defined culturally and internally, in terms of each culture’s own goals and aspirations. Each culture’s standards originate and develop from its particular needs and circumstances, not from a universal set of principles; so, Herder concluded, “let us have no more generalizations about improvement.”[6] Herder thus insisted “on a strictly relativist interpretation of progress and human perfectibility.”[7] Accordingly, each culture can be judged only by its own standards. One cannot judge one culture from the perspective of another; one can only sympathetically immerse oneself in the other’s cultural manifestations and judge them on their own terms.

However, according to Herder, attempting to understand other cultures is not really a good idea. And attempting to incorporate other cultures’ elements into one’s own leads to the decay of one’s own culture: “The moment men start dwelling in wishful dreams of foreign lands from whence they seek hope and salvation they reveal the first symptoms of disease, of flatulence, of unhealthy opulence, of approaching death!”[8] To be vigorous, creative, and alive, Herder argued, one must avoid mixing one’s own culture with those of others, and instead steep oneself in one’s own culture and absorb it into oneself.

For the Germans, accordingly, given their cultural traditions, attempting to graft Enlightenment branches onto German stock has been and would always be a disaster. “Voltaire’s philosophy has spread, but mainly to the detriment of the world.”[9] The German is not suited for sophistication, liberalism, science, and so on, and so the German should stick to his local traditions, language, and sentiments. For the German, low culture is better than high culture; being unspoiled by books and learning is best. Scientific knowledge is artificial; instead Germans should be natural and rooted in the soil. For the German, the parable of the tree of knowledge in the Garden of Eden is true: Don’t eat of that tree! Live! Don’t think! Don’t analyze!

For the Germans, accordingly, given their cultural traditions, attempting to graft Enlightenment branches onto German stock has been and would always be a disaster. “Voltaire’s philosophy has spread, but mainly to the detriment of the world.”[9] The German is not suited for sophistication, liberalism, science, and so on, and so the German should stick to his local traditions, language, and sentiments. For the German, low culture is better than high culture; being unspoiled by books and learning is best. Scientific knowledge is artificial; instead Germans should be natural and rooted in the soil. For the German, the parable of the tree of knowledge in the Garden of Eden is true: Don’t eat of that tree! Live! Don’t think! Don’t analyze!

Herder did not argue that the German way is the best and that it is justifiable for the Germans to become imperialistic and impose their culture upon others—that step was taken by his followers. He argued simply as a German in favor of the German people and urged them to go their own way, as opposed to following the Enlightenment.

Herder is relevant because of his enormous influence on the nationalist movements that were shortly to take off all over central and eastern Europe. He is also relevant to understanding how far from Enlightenment thinking the German Counter-Enlightenment was. If Kant is partially attracted to Enlightenment themes, Herder rejects those elements of Kant’s philosophy. While Herder is broadly Kantian epistemologically, he rejects Kant’s universalism: for Herder, how reason shapes and structures is culturally relative. And in contrast to Kant’s vision of an ultimately peaceful, cosmopolitan future, Herder projects a future of multicultural conflict. Thus, in the context of the German intellectual debate, one was offered a choice—Kant at the semi-Enlightenment end of the spectrum and Herder at the other.

References

[1] Barnard 1965, 18.

[2] In Berlin 1980, 14.

[3] Herder 1774, 188.

[4] Herder 1774, 187.

[5] In Barnard 1965, 54.

[6] Herder 1774, 205.

[7] Barnard 1965, 136.

[8] Herder 1774, 187.

[9] Herder 1769, 95; see also 102.

[This is an excerpt from Stephen Hicks’s Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault (Scholargy Publishing, 2004, 2011). The full book is available in hardcover or e-book at Amazon.com. See also the Explaining Postmodernism page.]

This explains the inability for people to pass judgment on Islam and its barbaric tenants. Especially with regards to Female Genital Mutilation. I know the practice predates Islam, however they have cooped this practice because it aligns with the religion’s views on girls/women. I have not heard any feminist groups on the Left criticize this practice. In fact they support implicitly due to multiculturalism. There has been an arrest in Michigan against male and female doctors who have been mutilating girls for years. I can see their defense: it’s cultural and a part of their religion, so therefore they shouldn’t be prosecuted. German philosophy has destroyed everything, literally and figuratively.

I can see one glaring difference between Herder and the contemporary university: Herder did not pathologically hate his own culture.

Also, are the academic multiculturalists really “relativists”? They seem to have erected their own hierarchy of cultures, with the West at the bottom.

Good point about the difference.