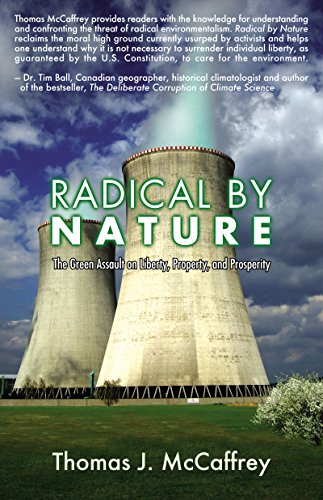

I’m reading Radical by Nature: The Green Assault on Liberty, Property, and Prosperity by Thomas J. McCaffrey.

His target is radical environmentalism. Environmentalism as a big-tent label like feminism, liberalism, and conservatism, each having many competing strands within. McCaffrey focuses on the most philosophically fundamental versions of envrionmentalism — and with good reason, as that version has had the most influence in determining environmental philosophy and setting policy.

McCaffrey is a clear writer, and his hefty volume contains strong summary histories of the several intellectual currents that fed into the radical environmentalist package: Progressivism’s undermining of the original classically-liberal basis of the U.S.A., along with contributions by Pragmatist philosophers and jurists, Romanticist philosophers, socialist-influenced economists, anti-modern traditionalists, and big-government-managerial political-theorists. All of that high theory made possible a cultural and political revolution that, in the specific domain of environmental policy, led to a series of shifting Supreme Court precedents and the formation of expansive new regulatory bodies.

Radical environmentalism’s core policy claim is that there is a zero-sum trade-off between economic health and environmental health. Therefore, economic health is the enemy.

One necessary result is the crafting of environmental regulations that will, for example, increase manufacturing costs domestically. The increased costs will of course give American businesses an incentive to relocate elsewhere and, consequently, to decrease employment domestically. But, MacCaffrey argues, those are features and not bugs of radical environmental policy thinking:

“Manufacturing jobs … tend to pay considerably better than service sector jobs. A country that loses manufacturing jobs and replaces them with service jobs will be a poorer country for it. But a poorer U.S. would be a more environmentally friendly U.S. The de-industialization of America is a direct–and intended–consequence of the environmentalist campaign.” (p. 512)

In addition to drawing out the startling economic consequences of such policies, McCaffrey argues that a morally-principled response to environmentalism is essential. We must reject the view that

“man should orient his actions around the needs of nature in general rather than around his own interests” (p. 519)

And his big positive claim is that such a moral re-orientation will be win-win, as a healthy economy and a healthy environment are mutually-beneficial. But a big philosophically-, economically-, and technically-informed battle is ahead of us. Reading McCaffrey’s book is useful preparation.

Related:

Blamestorming and Environmental Problems.

New York’s Biggest Toxic Dump: The Love Canal—Six Decades Later.

The Bhopal Chemical Spill Disaster — Who Is to Blame?

Environmentalist Mark Lynas’s lecture to Oxford Farming Conference.