I’m re-reading some biographical material on Kant, the great counter-Enlightenment philosopher of Königsberg. (Apparently, the crooked-timber house that Kant lived in early in his career was subject to vandalism recently. A sublime and phenomenal critique of the critiquer.)

With one exception, Professor Kant had no pictures hanging on the walls of his house. Kant had been raised in a strict Pietist household. Pietism is a version of Lutheranism that emphasizes spiritual inwardness, simplicity, and rejects external decoration and imagery.

The one exception for the adult Kant was in his study and directly over his desk: a picture of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. “I learned to honor mankind from reading Rousseau,” Kant said.

Unlike Kant, I have a large number of paintings in my study. But like Kant I have only one portrait in my study.

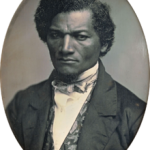

Mine is of Frederick Douglass. It shows Douglass in his late twenties, with his hair still dark and his visage of unbreakable purpose.  It’s a print from a daguerreotype made circa 1850. The original is at the Art Institute of Chicago.

It’s a print from a daguerreotype made circa 1850. The original is at the Art Institute of Chicago.

In the context of my ongoing competition with Kant, I very much like this symbolism: Rousseau versus Douglass.

Rousseau holds that man is born free and is now in chains. Douglass was born in chains and made himself free.

But Rousseau is concerned to justify our chained state. As he puts it in the opening section of The Social Contract: “What can render it legitimate?” And to do so, he proposes to yoke each of us to the collectivized General Will as administered by the State’s compulsive power: “whoever refuses to obey the general will will be forced to do so by the entire body; this means merely that he will be forced to be free.”

Further from Rousseau: “The state … ought to have a universal compulsory force to move and arrange each part in the manner best suited to the whole.” And if the state’s leaders say to the citizen, “‘it is expedient for the state that you should die,’ he should die.”[2]

Douglass’s purpose, by contrast, is to end bondage and achieve liberty for all. This from his letter to his former master on why he escaped from slavery:

“The morality of the act, I dispose as follows: I am myself; you are yourself; we are two distinct persons, equal persons. What you are, I am. You are a man, and so am I. God created both, and made us separate beings. I am not by nature bound to you, or you to me. Nature does not make your existence depend upon me, or mine to depend upon yours. I cannot walk upon your legs, or you upon mine. I cannot breathe for you, or you for me; I must breathe for myself, and you for yourself. We are distinct persons, and are each equally provided with faculties necessary to our individual existence.”[3]

For your personal collection, portraits of either man are available for sale. The choice is yours: Jean-Jacques Rousseau or Frederick Douglass.

Sources:

[1] Otfried Höffe, Immanuel Kant. Translated by Marshall Farrier (State University of New York Press, 1994), p. 17.

[2] Rousseau, The Social Contract, 1.1, 1:7, 2:4, and 2:5.

[3] Douglass’s 1848 letter from Frederick Douglas: Selected Speeches and Writings.

[4] My extended discussion of Kant’s philosophy and Rousseau’s politics is in my Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault.

Why do you speak of Kant as “Counter-Enlightenment”?

Why does it look as though Rousseau’s wife is trying to jump out of the window to get away from him?

Hi Elizabeth. Good question. For two main reasons.

One is that a major theme of the Enlightenment was to champion the power of reason against the pre-modern, Medieval emphasis upon tradition and faith. But Kant undercuts reason by arguing that it cannot know objective reality, only subjective constructs; and he is fine with that as he famously puts it in saying that showing the limits of rational knowledge makes room for faith.

The second is that the Enlightenment also made the pursuit of happiness a human moral birthright, in contrast to the previous era’s emphasis upon duty and selfless sacrifice. But Kant returns to making duty fundamental to ethics and denies the moral significance of happiness.

So on those two important Enlightenment themes, Kant is a counter to them.

I like that feature of the picture too, Irfan.